Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

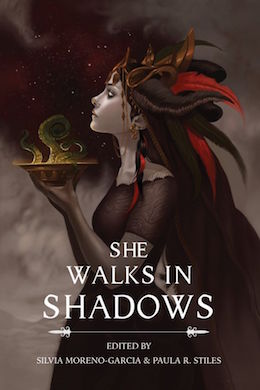

Today we’re looking at Amelia Gorman’s “Bring the Moon to Me,” first published in the 2015 anthology, She Walks in Shadows, edited by Silvia Moreno-Garcia and Paula R. Stiles. Spoilers ahead.

“The shadows in our house made me anxious. They came out of the corners when my mother sang and knit, and flew across her face and hands.”

Summary

Unnamed narrator remembers her mother knitting, turning yarn “into thick forests and spiraling galaxies” via patterns with such “luscious” names as Herringbone and Honeycomb and Tyrolean Fern. Their house “smelled fat with lanolin and fish oils,” and customers for her mother’s sweaters were many: fishermen from the nearby wharf, who smelled of grappa and spoke at a frequency that made narrator’s head buzz. The fishermen believed mother’s wares would protect them from the dangers of the sea. Narrator herself fears no storm, nor the “depths of the sea or the dark things that swam there.” It’s the shadows that gather around her knitting mother that make her nervous, and then there are her mother’s songs about shepherds and Hastur and the nighttime scent of lemon trees.

Mother thinks narrator works in a factory that makes blankets or rugs. Narrator can’t explain that she works instead as a programmer, that she and dozens of other women “weave instructions for computers” that will one day help the Apollo program reach the moon.

They are changing the world.

At work narrator absorbs numbers, recognizes patterns in the figures others do not. She carries the numbers home, “fat worms” that will eat holes in the side of her head so the zeroes fall out if she can’t “bring them into the tactile world.” Her mother’s birch needles are slowly rotting, for mother’s hands have swollen and knotted beyond plying them herself. Narrator takes them up and knits at seeming random, producing a “screaming wreck of different types of stitches,” here flat, there rough, with scallops “abruptly cut off.” Narrator thinks she’s the only one who can read this chaos of yarn, but her mother sees meaning as well, and they finally speak a common language.

Mother tells the story of a pattern she made only once. She sold it to a fisherman with the assurance it would protect him, but it actually served as “a beacon that shouted at the heart of the Moon.” The shout wasn’t loud enough to bring the Moon from the sky, but it did make the fisherman see sunken cities and the dead rising from the seabed, visions about which he still babbles.

Now mother whispers the beacon pattern into narrator’s ear. Narrator translates the stitches into machine language. The digital beacon will hide in the forest of code her colleagues weave each day. It will ride with Apollo into space, a “shining sign” to call something that lives beyond the moon.

When the astronauts return, they’ll bring with them an enormous shadow. “Its landing will send out ripples as large as the Pacific. Its hooves will trample the street lights and skyscrapers until there is nothing left but starlight.” Wrapped in her sweater, narrator will stand by the bay, the last one standing.

Her work will change the world.

What’s Cyclopean: The patterns have names like Herringbone, Honeycomb, and Tyrolean Fern—or Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo.

The Degenerate Dutch: Once all humans are trampled beneath the hooves of the shadow from beyond the Moon, you won’t be able to tell the difference between them. Won’t that be nice?

Mythos Making: Narrator’s mom sings about Hastur and the sweet smell of lemon trees. If those are in the same song, I have questions. (Mostly, “Can I see the lyrics?”)

Libronomicon: Books about Charles Babbage, George Boole, and Grace Hopper aren’t enough to help the narrator’s mother understand the power of programming.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Trusting cultist-made sweaters to protect you from the elements can be a dangerous gamble. Caveat emptor.

Anne’s Commentary

My summary of “Bring the Moon to Me” is half the length of the story itself, which comes in at a little over 1000 words. That speaks to the poem-intense density of Gorman’s prose—talk about packing a lot of content into a very small space. What’s still more admirable, she does it with grace, much more like Hermione caching entire houses and full-length portraits in her magical change-purse than like me, bouncing on a suitcase to smash in that last indispensable pair of jeans.

It was a nice bit of serendipity—or synchronicity—that we read “Bring the Moon to Me” the same week I went to see Hidden Figures. Too bad Gorman’s narrator isn’t the Team Humanity player that Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughn or Mary Jackson were. I mean, too bad for those of us on Team Humanity, however sporadically. Not that narrator is necessarily human, or entirely human, or your run-of-the-mill Homo sapiens.

Gorman mentions information age pioneers George Boole, Charles Babbage and Grace Hopper. She doesn’t name Margaret Heafield Hamilton, who led a team at the Charles Stark Draper Lab to develop software for the Apollo program, but her mention of people “weaving” commands for the moon launch made me think of Hamilton, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which is in Cambridge. Massachusetts. You know what’s also in Massachusetts, and features wharves, and kinda funky fishermen?

Yeah, I’ll go there. I’m going to posit that the narrator lives in Innsmouth, which would give her a fairly easy commute to Cambridge and the Draper Lab. [RE: I thought of that, but… earthquakes in the bay? Maybe Cthulhu is restless. AMP: Heh, the strongest earthquake I’ve experienced was sitting on the back deck at Harwich on Cape Cod. But that could have been Cthulhu as well.] The oddly mumbling and fishy-smelling people of Innsmouth knot nets to earn their livings, and Mother knits sweaters to protect them not merely from the cold and wet but from all the disasters that may befall the hazardous profession. She’s a yarn-witch who transforms abstract magical patterns into woolly materiality, wearable spells of warding or (more ominously) calling. Narrator works in the abstract realm of numbers, but she can transform patterns of the “simplest” of them, zero and one, into commands—spells—powerful enough to propel real live humans encased in a metal cocoon all the way to a hunk of rock floating in space. She and Mother could be Deep Ones, like their customers. In which case what cripples Mother’s hands might not be arthritis. It might be slow transformation. No wonder narrator’s not scared of the sea and its dark denizens. Sea-salt’s in her blood, and she may be a dark denizen herself one day.

And yet. It’s not of Cthulhu or Dagon or Hydra that Mother sings, nor of the glories of Y’ha-nthlei. She’s more into Hastur and lemon trees—and shepherds. That last implies that we’re talking about the first Hastur, the god of sheep-tenders Ambrose Bierce created in “Haita the Shepherd.” But who knows? Hastur’s all over the place. He could be the King in Yellow, or progeny of Yog-Sothoth and half-brother of Cthulhu. Pratchett and Gaiman make him a duke of Hell. John Hornor Jacobs has him playing a particularly insidious form of the blues. Marion Zimmer Bradley would have him (and Cassilda) the founder of a Darkover house. Then there’s our anime-friend Nyaruko, who hangs out with fellow Mahiro-admirer Hastur, a cute blond boy who wields wind magic.

That complexity and confusion is the Mythos-that-is, I guess, rather than the Mythos some of us are tempted to formalize into a shared universe with absolute canon. Your Hastur doesn’t have to be mine, or Gorman’s either. Here he may be just a bit of color, and that’s cool too.

Though Hastur is the only out-and-out Mythos reference in “Bring the Moon to Me,” the story’s Mythosian savor is strong. There’s the cosmic-force-waiting-to-return thing. There are the underwater city and sunken dead the beacon-wearing fisherman sees, not Y’ha-nthlei perhaps, but the drowned metropolis and sailors of “The Temple” or an aqua-town of the Dreamlands seas. There are the hooves of the Shadow from the Moon, which must call to mind (mine at least) our Lady of a Thousand Young, Shub-Niggurath.

I don’t know if Amelia Gorman knits with yarn, but she’s certainly gifted at knitting with words and images. I especially like the close of “Bring the Moon,” in which narrator stands by the bay, last person still on her feet. Apart from standing, she wraps what around her shoulders? Her sweater, of course. Is it one Mother made her long ago or the one whose pattern Mother whispered in her ear, whose digital translation is the beacon of apocalypse? I’m going with the latter sweater, and I hope that the Shadow recognizes in this humble garment the ceremonial cloak of Its priestess, thus herself a beacon.

What would the Shadow do to its Priestess, though? Elevate her as chief (sole?) Shadow-Worshipper? Step on her as now superfluous? Who knows what Shadows want? I hardly know what I’d want for the narrator. One hand, she’s intent on screwing up humanity’s plans for all eternity or at least the foreseeable future. Other hand, hers is such a grand egocentricity, eschewing “We’re changing the world” for “My work will change the world.” Third hand, maybe we have enough egocentricity to chew on for the moment, right here in Real World City.

Fourth hand, I’m in the market for a nice new sweater. Is Mother on Etsy?

Ruthanna’s Commentary

The idea story has a long and noble SFnal history, now mostly past. The golden age authors, none of whom cared to characterize their way out of paper bags, excelled at them. Characterization wasn’t the point: get in, share your clever tech concept or mindblowing idea about parallel universes, and get out. The reader gets a quick shot of sensawunda, the writer gets a quick paycheck. For the horror writer, the focus of the short-short is mood rather than idea—Lovecraft has a few good ones himself—but in either case, emotional impact is for the reader, not the characters.

She Walks in Shadows, an anthology of Lovecraftian stories by and about women, is not where I would have expected to find an idea story—or even just its surface form. Four brief pages long, “Bring the Moon to Me” could be excused if it did nothing more than follow the grand tradition of “Nightfall” and “Nine Billion Names of God.” Clever new methods of imanentizing the eschaton don’t come around every day, after all. But in addition to your everyday textile-based elder god summoning ritual, Gorman fits in some sweet characterization. Even cultists, it seems, are prone to fraught mother-daughter relationships, and difficulty communicating across technological gaps. Having recently talked my mom through the set-up on her new e-reader, I can totally relate.

“Moon” is, in fact, a perfect fit for the anthology. Not only are the characters women, but traditionally female arts play an unexpectedly dangerous part. The mother knits protective sweaters for fishermen—possibly for fishermen who go out to chat up Deep Ones? They mumble at head-buzzing frequencies, so presumably they have some reason for purchasing their windbreakers from a Hastur cultist and not, say, Macy’s. The daughter, in turn, is a computer programmer during the brief period after looms suddenly developed world-shaking powers, but before the male of the species decided to up the associated salary and claim the art for himself. (If I’d made it to “Hidden Figures” yet, I’m sure I’d be full of crossover plot bunnies. Since I haven’t, I’ll leave that to the comments.) [ETA: Or to my co-blogger. Maybe I’ll get my movie night as a reward when I finally finish the draft for Innsmouth Legacy 2.] These days, we tend to forget that programming started as a textile art, and that there’s a reason geekdom is full of both computer nerds and knitters. Knit one, purl two, knit one; one, zero, zero, one.

And magical spells are often supposed by modern fantasists to be akin to programming. Mysterious languages, difficult for the layperson to pronounce, changing the shape of reality through exact phrasing and pronunciation. Gods defend you if you use the wrong word. It follows, then, that they can be woven as easily as typed. Narrator sees the connection, and worries about her binary numbers “turning into fat worms and eating holes in the side of my head.” That seems like a very Mythosian fate.

What of the thing in the moon, that she and her mother are trying to call down? The thing that tramples cities and sends tsunamis across the pacific? Mom sings about Hastur, and it could be Hastur. Or the Goat With a Thousand Young—the moon is so often seen as maternal. Or any of the named and nameless godlike entities sleeping in one or another corner of Lovecraft’s universe, waiting for the stars to be right. Like good cultists everywhere, narrator lives to serve, and is content to be eaten last as her humble reward.

This, people, is why you always get more than one programmer to check your code before you ship. You never know when one of your team might be secretly putting in back doors for hackers. Or for eldritch abominations imprisoned for aeons beyond the moon, waiting for just the right function call to break free.

Next week… actually, first of all, this week, Anne and Ruthanna will be at the American Writers Program conference in DC. At 12 PM Thursday we’ll be on “The Infinite in the Finite: One Hundred Years of H.P. Lovecraft’s Legacy,” attempting to sound erudite and giggling madly over cyclopean counts. Sometime over the weekend, we’ll also bond over Lovecraft and Adolphe de Castro’s “The Electric Executioner.” We’ll tell you all about it next week.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.